"Michael Bloomfield was so much more than a great guitarist. Raconteur, musicologist, renaissance man, mensch, painter, ultimate appreciator are some of the words used to describe him. I've heard it said often that if you knew Michael, you were changed by him, and that when he walked into a room, his charisma and energy made it difficult to focus on much else."

–Bill Keenom

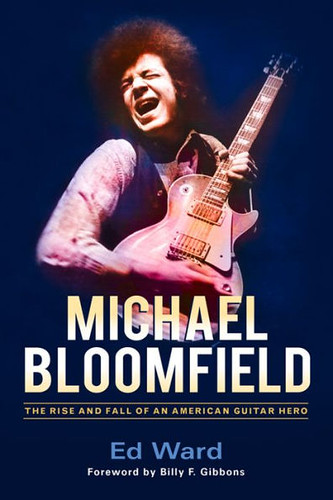

Last summer I read a book entitled

Michael Bloomfield: The Rise and Fall of an American Guitar Hero by Ed Ward, and wrote about it briefly in a

blog post dated July 10, 2018. I've been a fan of Bloomfield's music for decades, and after reading this book, I knew I needed to read more.

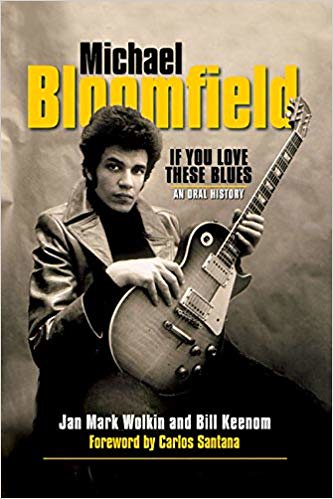

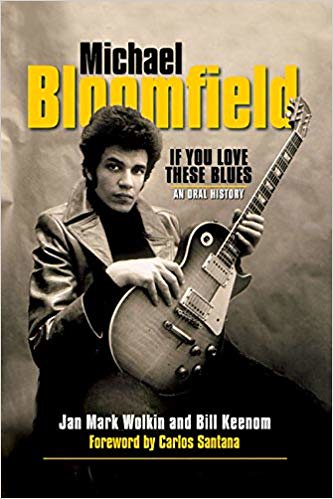

The search took me a while, but eventually I tracked down a copy of

Michael Bloomfield - If You Love These Blues: An Oral History

by Jan Mark Wolkin and Bill Keenum. My hardcover copy was missing the compact disc that is supposed to accompany the book. The paperback edition doesn't have a CD, but the publisher, Hal Leonard, provides a URL on the back cover so that the reader can access the music online. One problem: The URL is not valid. I've written to the publisher about this, but so far, a week later, I have not received any response.

The subtitle of this book is "An Oral History": the entire book consists of excerpts from interviews with Bloomfield's bandmates, producers and promoters, roommates and friends, and family (including his ex-wife). And, of course, the guitarist himself. The majority of these interviews were conducted by the book's authors, but some, as in the case of Bloomfield, were from prior interviews as the book was published in 2000, and Michael passed away in 1981. But what makes this book unique is that the interview excerpts are provided in chronological order, with excerpts from two or more individuals regarding specific events so that the reader can experience this from multiple viewpoints.

I just counted the markers -- nearly 20 of them -- I placed on various pages in the book denoting quotes that just had to be shared when I wrote this post. Obviously, far too many, but I'll see what I can do about narrowing them down to a very important few.

"When I came back through Chicago in '62, [Michael] took me down to the South Side to hear some music. He said, 'Man, you've got to meet Muddy.' So we go to Pepper's Lounge, and Michael walked right up to the bandstand and said, 'Hey, Muddy.' Muddy says, 'Hey, Michael, how're you doing?' And Michael says, 'I'd like you to meet my friend John Hammond.' I felt like I was going to fall down. And then, in the middle of Muddy's show, he calls Michael up to play with him. I was mind-boggled. And Michael was great. He knew all the details of cool stuff. He was a wonderful guy. I valued his friendship more than I can ever say. He was just a terrific person."

–John Hammond Jr.

"...There were other musicians, but Michael was the first one that I befriended and who befriended me. He was a Chicago guy, I'm a New Yorker, and we hit it off, personality-wise. Michael was quick and very witty. And we were able to jabber on easily....[Michael] always had somebody that he was pushing. It if wasn't the Staple Singers, it was Albert King or B.B. King or Otis Redding or Howlin' Wolf. He, more than any single musician, kept bringing me records and mentioning groups to me. Prior to 1965, I knew nothing. I wasn't in the rock & roll world. It wasn't part of my private life. I'm a Latin music fan, a jazz fan of sorts, but I never listened to blues much or rock & roll at all. I think the music industry owes Michael far more than they realize. Besides being a very special musician in what he brought out of the guitar and how he made people feel. I don't know if I would have been that successful early on if it wasn't for Michael, his knowledge and his awareness and his prodding me to bring these artists to the Bay Area. So, as great a guitar player as Michael was, he was really a teacher."

–Bill Graham

"When Michael first came to San Francisco, for some reason, he befriended me. I had just started to play with the Jefferson Airplane, and I'd never played electric guitar before, really. He showed me how to bend notes, and to feedback and sustain things, and I was really thrilled. Because in those days some of the East Coast guitar players were very guarded about their secrets and the way they did stuff. I knew guys who used to turn away from you when they played so you couldn't see how they were doing it. Michael was a really sweet guy and a brilliant guitar player, and he was really instrumental in getting me into being an electric guitar player."

–Jorma Kaukonen

"Around December 1968, Michael and Nick Gravenites helped Janis Joplin set up the Kozmic Blues Band. Janis had left Big Brother. She was very frightened about what she was going to do about putting a band together....They came in, and Michael took the time to make everyone feel good, and they whipped that band together really quick. He was kind of like an A&R man. He selected the tunes—a lot of them were Nick's—and then he went on and made sure everyone could play them. We had other music directors who were really unessential. Michael was really the one who put it together. Michael played on a few of the Kozmic Blues tracks. I still get people come up to me, if they're real sharp, young guitar players, and they'll say, 'Was that you playing on "One Good Man"?' I'll say, 'No, that was Michael,' and they'll go, 'I knew it! I knew it!'"

–Sam Andrew

"When I was 17, I thought I was good enough to gig in black places and hold my own. You had to hold your own. If you shucked, then you had no business being there. You'd not only be a white kid, you'd be a fool. You'd be a punk and a fool....Several guys took me to be almost like I was their son—Big Joe Williams, Sunnyland Slim, and Otis Spann. They took me to be like their kid, man; they just showed me from the heart. They took me aside and said, 'You can play, man. Don't be shy. Get up there and play.' What I learned from them was invaluable. A way of life, a way of thinking, a whole kind of thing—invaluable things to learn. I used to hear Elmore James, Sonny Boy, Little Walter, Howlin' Wolf, Muddy Waters, Freddie King, Albert King—way before they were known anywhere but the ghetto....I was interested in it from a musicological standpoint. I was trying to discover where the old blues singers lived. I met cats like Washboard Sam and Jazz Gillum and Tommy McClennan and Kokomo Arnold. I used to have a band with Big Joe Williams....By then it was a scholarly thing. Like Paul Oliver and Sam Charters, I wanted to know the story of the blues, and the best way for me to learn was to actually meet the guys."

–Michael Bloomfield

"In 1969, I produced the Fathers and Sons album. We brought in all these great players: Muddy Waters, Otis Spann, and this great band—all in the Chess studio. I had Michael, Paul Butterfield, Buddy Miles, Duck Dunn, Sam Lay, and every blues musician in Chicago. Michael named it. He said it should be called Fathers and Sons, because that's how he related to Otis Spann and Muddy. He gave me that title, and he insisted that that's what it be."

–Norman Dayron

In my previous Bloomfield blog post, I state that the guitarist died alone in his car from an apparent cocaine and methamphetamine overdose: two drugs that Michael would never touch. So the question remained: Why?

In this book, through interviews with Christie Svane, Michael's girlfriend at the time of his passing, I learned what may have driven the guitarist further into the darker realms of loneliness and despair. And Norman Dayron speculates as to why cocaine was found in Michael's system after his death, a drug that Norman knew Michael absolutely refused to use. Again, it's all speculation, but indeed quite plausible.

Michael Bloomfield - If You Love These Blues: An Oral History

by Jan Mark Wolkin and Bill Keenum (Miller Freeman Books, 2000, 280 pages).

This is the first mystery I've read in a very long time, and especially one that kept me reading, page after page, wanting to learn what happens next.

This is the first mystery I've read in a very long time, and especially one that kept me reading, page after page, wanting to learn what happens next. by Andrew Cartmel (Titan Books, 2016) is the first volume in an ongoing series that currently numbers four -- and I already have book number 2 on order.

by Andrew Cartmel (Titan Books, 2016) is the first volume in an ongoing series that currently numbers four -- and I already have book number 2 on order. .

.