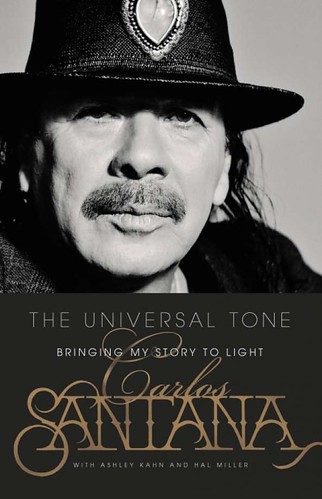

The book was published in 2014 by Little, Brown and Company. NPR (National Public Radio) named The Universal Tone one of its Best Books of 2014. It received a starred review in Kirkus (and anyone who knows Kirkus, knows that it's nearly impossible to even get reviewed by Kirkus!). And the book went on to win the American Book Award in 2015.

From Chapter 20:

In a funny way, my life has always been local—everything that happens comes from where I am. John Lee Hooker was living in the [San Francisco] Bay Area at this time. He was the Dalai Lama of boogie. Shoot, he should have been the pope of boogie as far as I'm concerned. We got to know each other. A lot of times we'd be playing, and he'd say, "Carlos, let's take it to the street," and I'd say, "No, John, let's take it to the back alley," and he'd say, "Why stop there? Let's go to the swamp." I miss him so much.

A John Lee boogie pulls people in as strongly as gravity holds them to this planet. He is the sound of deepness in the blues—his influence permeates everything. You can hear him in Jimi Hendrix's "Voodoo Child (Slight Return)" or in Canned Heat's boogies. That's nothing but John Lee Hooker. When you hear the Doors, that's a combination of John Lee and John Coltrane. That's what they do; that's the music they love.

...

In '89 John Lee was local to the Bay Area. He was living not far from me, in San Carlos, which is near Palo Alto. We met a few times and talked, and at some point he actually invited me to his house for his birthday, which was the first time I really hung out with him. I brought a beautiful guitar to give him.

When I walked in, I saw that everyone was watching the Dodgers on TV, because that's John Lee's favorite team. He was eating fried chicken and Junior Mints. No kidding—Junior Mints. He had two women on the left and two on the right, and they were putting the mints into his hands, which were softer than an old sofa. I stepped up and said, "Hi, John. Happy birthday, man. I brought you this guitar, and I wrote a song for you."

"Oh, yeah?"

"It sounds like the Doors doing blues, but I took it back from them and I'm returning it to you and I'm calling it 'The Healer.'

John Lee chuckled. He had a slight stutter that was very endearing. "L-L-Let me hear it."

I started playing, and I made it up right on the spot—I knew how he did the blues, how he played and sang. "Blues a healer all over the world..." He took the song, and when he recorded it, he added to it in his own way. I said, "Okay, we've got to go to the studio with this, but I just want you to come at one or two tomorrow afternoon, because I don't want you to be there all day, man. I just want you to come in and just lay it. I'm going to work with the engineer—get the microphones ready, get the band to the right tempo. You just show up."

"Okay, C-C-Carlos."

When John Lee showed up we were ready. I got the band warmed up—Chepito, Ndugu, CT, and Armando—no bass, because Alphonso didn't make that gig. John Lee and Armando were checking each other out like two dogs slowly circling each other—they were the two senior guys there, and you could really tell that Armando needed to know who this new older guy was. He was looking at him slowly, all the way from his feet up to his hat. Just sizing him up. John Lee knew it, but he just sat there, tuning his guitar, chuckling to himself.

Armando threw down the first card. "Hey, man, you ever heard of the Rhumboogie?" He was talking about one of the old, old clubs on the black music circuit in Chicago, opened by the boxer Joe Louis back before I was even born. John Lee said, "Yeah, m-m-man. I heard of the Rhumboogie." Armando had his hands on his waist like, "I got you now." He said, "Well, I played there with Slim Gaillard."

"Yeah? I opened up there for D-D-Duke Ellington."

I saw what was going on and stepped in. "Armando, this is Mr. John Lee Hooker. Mr. Hooker, Mr. Armando Peraza."

We did "The Healer" in one take, and the engineer said, "Want to try it again?"

John Lee shook his head. "What for?"

I thought about it and said, "Would you mind going back in the booth, and when I point at you, would you be so gracious as to give us your signature—those mmm, mmm's?" John Lee chuckled again. "Yeah, I can do that." I said okay. That was the only thing he overdubbed that day—"Mmm, mmm, mmm."

"The Healer" helped bring John Lee back for his last ten years. He had a bestselling album and a music video—everything he deserved. We started to hang out more and play together. I would see him in concert, too. He had a keyboard player for many years—Deacon Jones—who used to get up onstage and say, "Hey! You people in the front—you might need to get back a little bit, because the grease up here is hot. John Lee's about to come out!" I have so many stories like that as well as stories about John Lee calling me—sometimes during the day, but, like Miles [Davis] did, mostly late at night.

I remember John Lee opening for Santana in Concord, California, and we had finished our sound check and he'd been waiting for me on the side of the stage. We were done, and he started talking to me while we walked away. The soundman came running up. "Mr. Hooker, we need you to do a sound check, too."

"I don't need no sound check."

"But we have to find out how you sound."

John Lee kept walking. "I already know what I sound like." End of discussion.

on August 23, 1994.

on August 23, 1994.